Why How to Shoot Matters

I didn't really think about it until I thought about it. Then I Did Something About it.

I didn’t set out to make a “how-to” series. The irony of the title is deliberate—How to Shoot isn’t about step-by-step tutorials or technical cheat-sheets, but about situating photography in the crosshairs of practice, history, and authorship. The photographer doesn’t merely “take” a picture. They shoot—wrestling with the violent and ethical act of pointing a camera at another human being, or a landscape, or a moment in the city.

In On Photography, Susan Sontag wrote: “To photograph people is to violate them… it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.” This tension—between image-making as participation and as violation—runs through the bones of the How to Shoot series. I’m less interested in the glossy manuals of exposure and more interested in what it means to stand on a street corner in Hollywood, camera at the ready, and decide what deserves to be seen.

How to Shoot

The core of the series begins here. Not as a manifesto, but as a provocation: photography is not neutral. To shoot is to impose. Henri Cartier-Bresson framed it as “the decisive moment,” but Garry Winogrand countered with his relentless flood of frames, showing that decision is itself a philosophical position. My project asks—what does it mean to decide now, in an age where every image collapses into infinite feeds?

The text and images work together to destabilize the easy comfort of image-making. This isn’t a craft book—it’s a mirror.

How to Shoot Women

The second chapter, How to Shoot Women, doesn’t shy away from the most difficult of questions: the historical and ongoing objectification of women in photography. From Weston’s nudes to Helmut Newton’s glossy fetishism, the female body has long been the surface upon which photographers assert authority.

My task here is not to condemn or to excuse, but to trouble. Following Laura Mulvey’s famous essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” I turn the camera back onto the photographer and insist on accountability. When I photograph women, am I co-authoring an image or am I perpetuating an archive of male gaze? When I turn the workshop into dialogue, am I teaching students how to see differently, or teaching them how to repeat the past?

The answers aren’t simple—but that’s the point. To shoot women is to confront the apparatus itself.

Hollywood Street

The Los Angeles strip in Hollywood Street is more than neon and decay—it is a theater of spectacle. To walk Hollywood Boulevard with a Leica is to recognize that everything is already staged, already artificial, already begging to be photographed.

Walter Benjamin described the flâneur as the detached observer drifting through the city. But in Los Angeles, the flâneur is swallowed by spectacle; the observer becomes part of the performance. When I teach this section, I ask participants to dissolve into the crowd, to become invisible in order to capture the visible. It’s less about photographing actors and more about recognizing that we are already in a film.

The “street” here is not documentary—it’s hallucination.

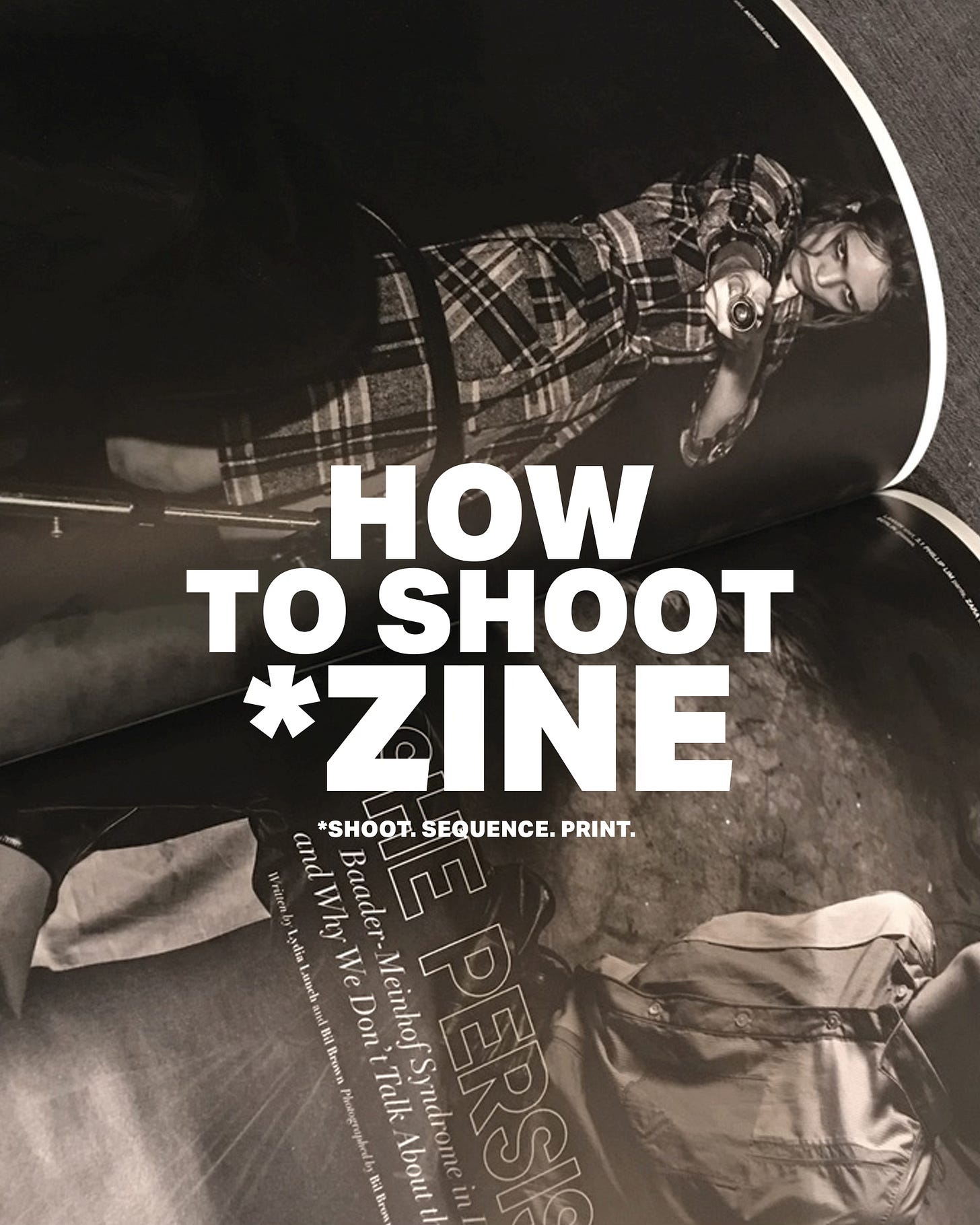

The Zine Lab

The Zine Lab emerged from a dissatisfaction with the gallery and the screen. Books and zines remain one of the last democratic spaces for images to live and breathe outside the algorithm. The zine is not merely an object—it’s a tactic, a form of resistance.

Drawing on my early days at Naropa, in the lineage of the mimeograph revolution of the Beat poets, I reimagine the photo zine as a way of giving the image back to the street. Artists like Daido Moriyama proved this with Provoke, where the grainy page became the battlefield of thought. In The Zine Lab, students and participants aren’t just learning InDesign or folding paper; they’re learning how to make photography circulate in the world on their own terms.

After the Street

Finally, After the Street asks what happens when the act of shooting is over. When the adrenaline drains. When the light is gone. What do we do with the image?

This is the hardest part, because photography doesn’t end when the shutter clicks. The photograph is a haunted object. It carries the weight of what Barthes called “that-has-been,” the reminder that every photograph is also a death. To teach “after” is to teach responsibility. To sit with the image, to edit, to contextualize, to give it life beyond the feed.

Why How to Shoot Exists

The How to Shoot series is not a curriculum in the traditional sense. It is a provocation, a challenge to photographers, artists, and cultural workers to reconsider what it means to make an image in 2025.

We live in a time when every gesture is surveilled, every image is commodified, every archive is contested. To photograph is to enter a battlefield. How to Shoot gives you the survival kit—not to win the war, but to keep walking, seeing, making, questioning.

The series is my way of insisting that photography is not decoration. It is an act.