The Image in Crisis Part 2: PHOTOGRAPHY AS PRESENCE

Let the Pictures Take You: Charles Harbutt, Aliveness, and the Collision Between World, Body, and Machine

Series: The Image in Crisis — Part II

“I don’t take pictures; pictures take me.”

—Charles Harbutt

If Sontag warned us that photographs turn people into objects, Harbutt asked us to consider the opposite possibility:

What if photography could turn the photographer into a vessel—an instrument through which the world reveals itself?

What if the photograph wasn’t a product of intention, branding, or design… but of collision?

You, the camera, the world—all slamming into each other for a fraction of a second. The shutter blinks, and something alive is caught—not captured, but invited.

In a culture obsessed with performance and control, Harbutt’s perspective feels almost mystical.

Photography, he argued, is less an act of making than of being available. Available to what the world offers. Available to being moved. Available to letting the picture take you.

I. Realness Without Strategy

In 1972, Harbutt stood before a crowd and said something radical:

Photography is not art.

It’s not fiction.

It’s not fantasy.

It’s not even memory.

Photography, at its core, is a real event. A visual manifestation of light bouncing off something that existed—once, just then, no longer. The medium’s uniqueness, he insisted, lies in its direct relationship with reality.

In a world where everything is filtered, arranged, monetized, or AI-fabricated, Harbutt’s clarity cuts deep. The photograph is not a simulation. It is a trace. A ghostprint. It only happens if you are there—if the camera is there—if light is there—if something real happened.

But presence is not just physical. It’s energetic. Emotional. Spiritual, even.

When I shoot in the street, or in a studio charged with eroticism or uncertainty, I try to enter what Harbutt called the existential photographic moment—before the mind decides, before the eyes design. When the image arrives from below thought. When the photographer doesn’t pose, but responds.

II. The Hypercube of Presence

Through the hypercube lens, we can map Harbutt’s ethic across dimensions of image-making:

1. Symbolic:

The image is not an idea—it’s a response. Not a message, but a mark left by experience. You don’t tell people what to see. You show that you were there.

2. Political:

To be fully present in a world that flattens you into a role or brand is political. It’s resistance to performativity. Especially for marginalized bodies, to be seen without staging, without armor, without agenda, is a radical gesture.

3. Mythic:

Harbutt becomes the seer, not the sculptor. The one who waits, wanders, witnesses. The photographer is not a god—but a shaman on the edge of clarity.

4. Sensory:

The click of the shutter is not mechanical—it’s orgasmic, as he wrote. It’s the intersection of stimulus and instinct. A felt knowing. Seeing becomes sensation.

5. Economic:

There is no economy of presence. You can’t package what disappears in a blink. Presence resists commodification. That’s why it’s so rare now. And so vital.

6. Temporal:

Photographs preserve a moment—but not like a freezer preserves meat. They preserve the feeling of a moment. The weight of time passing. The loss inherent in living.

7. Subconscious:

The best images are accidents. They arrive from the place beneath ego. Where memories, fears, and dreams flicker behind the eye. A photo catches something before you even know why it matters.

III. How Presence Looks: Mylar, Street, and the Missed Frame

In my MYLAR series, I work with the distortions of light and surface not just to fragment the subject—but to mirror their presence. Not as they want to be seen, but as they arrive in that moment. Sweaty, unstable, intimate. The image doesn’t explain them. It holds them like a bruise.

On the street, presence is even more vital. There’s no second chance. I learned this watching Bruce Gilden stalk the sidewalk—never asking, never waiting, just responding. Not because he didn’t care, but because he was there. Alert. Open. Present. The moment strikes—you strike back.

And sometimes the best photographs are the ones you don’t take.

The ones that pass.

The ones that didn’t want you.

That’s presence too.

Knowing when not to impose. Knowing that not everything must become image. Knowing that being present is enough.

IV. Toward a Ritual of Seeing

Harbutt’s photographs aren’t elegant. They’re not always beautiful. But they are alive.

That aliveness is the ritual.

He says the camera is a filter. Not a tool of domination—but a mediator between the world and the soul.

The best photographs don’t happen when you’re looking for them. They happen when you stop trying. When your camera is ready, but your mind is not in the way.

To photograph this way is to say yes to whatever comes. It’s not about control. It’s about contact.

It’s the eye as open palm.

“The fullest experience of life is possible only when one is awake and with open eyes, out on the streets of the world.”

—Harbutt

Closing: What Lives in the Frame

What Sontag framed as violation, Harbutt reframes as communion.

To photograph is not to own. It is to be touched—by what passes.

This is the antidote to content. To performance. To simulation.

Let the picture take you.

And let it remind you—you were alive.

Just then.

Just there.

One More Thing:

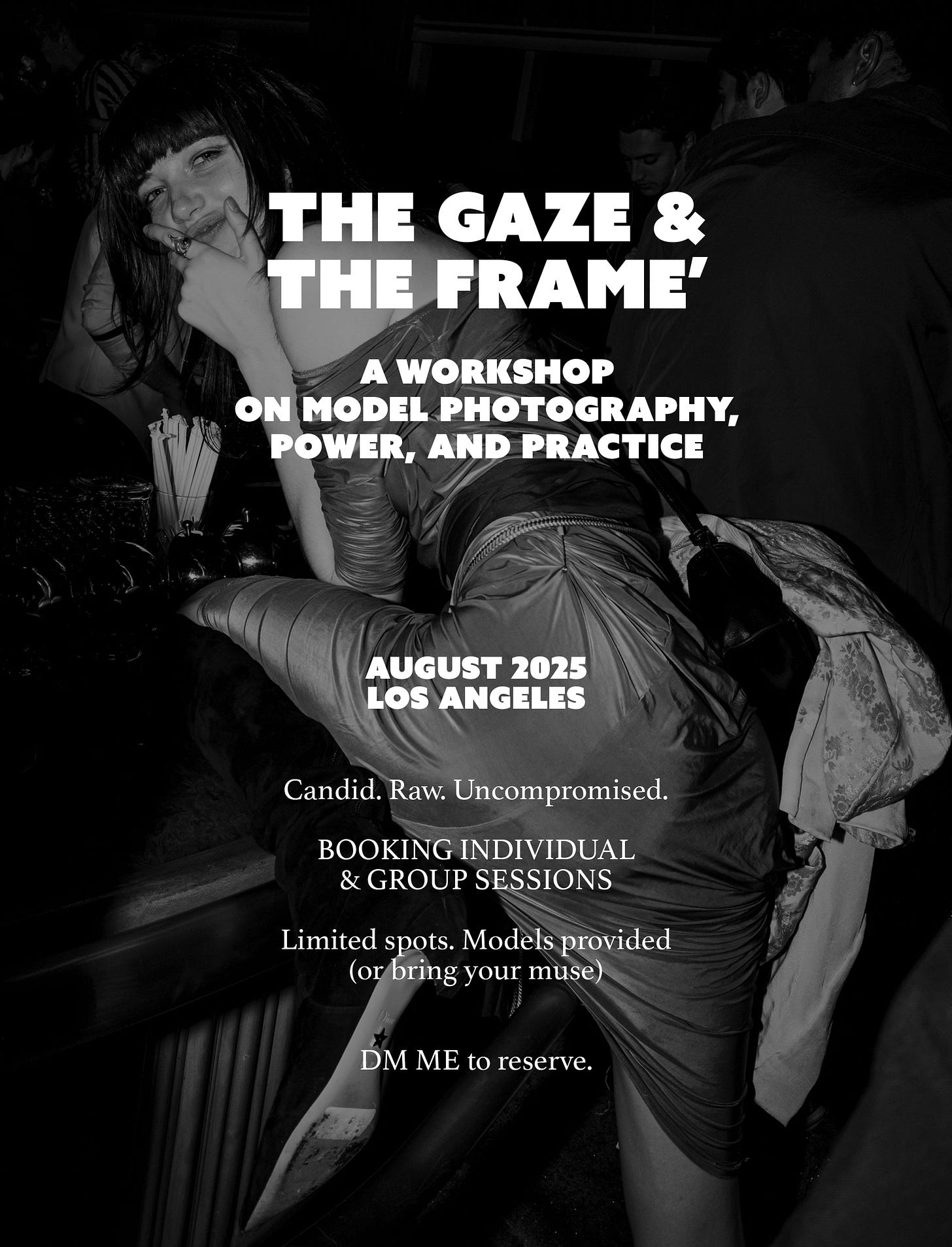

Next Month: GAZE AND THE FRAME — A Workshop in Los Angeles

Talk, Panels, Models and Photographers.

August 29, 2025

Image culture isn’t neutral. Modeling isn’t innocent. The gaze still has teeth.

This is a workshop about how power moves through the lens. It’s about desire, authorship, glamour, and control. It’s about who gets seen, how, and why.

And how we can shoot back.

Los Angeles

General Admission + Tiered Participation Options

Let’s make meaning, not just content.

Let’s reclaim the frame.

Next in the series:

THE IMAGE AS WOUND—Roland Barthes and the return of the punctum in a world of AI, loss, and images that no longer mourn.